The holiday season can be full of comparisons. What did we do last year for Christmas dinner? Is my partner buying me more gifts than I am for him? Why does my front yard look so bare when my neighbor’s lawn looks so jolly?

Comparisons can be particularly troublesome when I compare my mothering to the mothers I see on social media or the drop-off line at school. Am I giving my son the same magical experience this season that other parents do? Am I making sure my son has exposure to a diverse range of holiday traditions as other multi-racial families would share with their sons?

These questions can be exhausting and too focused on the external self.

So, what’s a more flexible response than comparison this season, one that focuses on my core self?

My teacher, Anjana Deshpande, at the Center for Journal Therapy shared with me that “Compassion is very practical, active and lives in the present moment. It is not about giving yourself a break, but seeing yourself in a more realistic light.

So when we say things to ourselves such as ‘Why am I not further along?,’ compassion will ask practical questions such as ‘Well, do you have more on your plate now than you did two years ago? Then why are you expecting to move at the same pace?’

Compassion helps us move away from comparisons (even with our old self) . . . and focuses on our journey right now.

Compassion is a skill that can be cultivated, and lives in our pre-frontal cortex, which means we have to get out of our emotional brains and into our rational brains where problem solving and solutions live.”

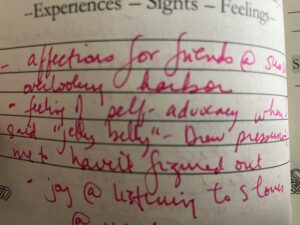

Here’s a journaling prompt to help you move from comparisons to self-compassion this winter season:

Write a compassionate description of yourself from the point of view of someone who loves you (could be your dog!). Or a description of yourself from the third person. Remember to focus on your core self! Describe how someone might see you physically, emotionally, spiritually. Paint a portrait with words. (Prompt written by Anjana Deshpande).

I wrote a character sketch of myself from the perspective of my five year old son. While I saw myself as too “woo-woo” and sometimes selfish (as compared to other moms in my life), I imagined my son saw me differently:

He sees a mommy in love with the outside world, the small things. He tells me: Stunning pancakes mom. Massaging spaghetti Mom. Mom, do you see the orange and yellow leaves? Did you see our baby trees growing? Stunning planting of roses, Mom.

He sees a woman who centers her life around beauty, makes it her prayer, and he prays along. He prays: May I get to see Grammy and Pop Pop soon. May Grand Judy get the stone out of her belly soon. May Baby Judah learn from me, his big brother.

He sees a woman living in the sensory way. I say: Let’s read this poem aloud Remi Bear right here on this sidewalk. Let’s share this coconut and chocolate bar together. Let’s help each other put on our gloves so we can pick up these pine cones.

I am aware that I am hard on myself as a mother, and that when I look at myself through the lens of my five year old son, I soften. I am dynamic. I invite connection. I am surprised at how much we are learning together as mother and son. I am surprised by how much positive influence I have on my son, including his desire to pray, to connect with his spiritual self, and his desire to be in the sensory way with me, although his responses lean towards the joyful (and my responses towards the bittersweet).

This is my prayer for you this winter: May you feel the good work of having a self-compassionate lens—the intentionality, the rationality of looking at yourself from various angles, and the shift to a problem-solving approach.

May you enjoy the cookies made with love—the thumbprints, the peanut butter blossoms, the gingerbread men, the toffee brittle bars.

Can’t wait to chat again in 2025!